As a four-year old I remember wondering if my dad would allow me to have the fish teeth left on his dinner plate after he consumed the edible part of the animal. I remember my dad catching a Mussel cracker at Sedgefield beach and wondering if he would allow me to keep the teeth. Two weeks later I had Mussel cracker jawbones as part of my growing collection of bones. I started collecting everything from chicken drumsticks to sheep rib bones. I remember a specific incident when my mother got a shock when she followed a trail of ants to my bedside drawer, only to find it stuffed with animal leftovers that included, fish bones (lots of fish teeth), chicken bones and bird skulls.

One day my cat brought a dead mole into the house. By this time I was old enough to realise that to get the bones from an animal, one either had to cook it in a pot in the kitchen, or bury it in our garden compost heap to rot away. My mother was not keen on the cooking idea, so the compost route was followed. This was not successful as the dead mole was dug out and eaten by other scavengers at night. I was quite disappointed after this first attempt failed, but decided not to give up and hoping that the cat will catch another mole. Fortunately this happened soon afterwards when another mole landed on our lounge carpet. This time around I placed the corpse in my dad’s earthworm compost bin where it was safe from stray cats. Two weeks later the earthworms have cleaned the animal and I started with the task of collecting the bones with tweezers. Every single vertebra, rib bone and claw was collected. With the help of my dad we started assembling the skeleton with superglue and paper. At the time I did not know much about the construction of skeletons. We tried searching on the internet, but were unsuccessful in our search for a golden mole skeleton. When I look at that first skeleton today, I feel a bit ashamed, because the pelvis position is totally incorrect. This was however my first complete skeleton of an animal. Much later I had another chance at constructing a golden mole skeleton. The skeleton is below.

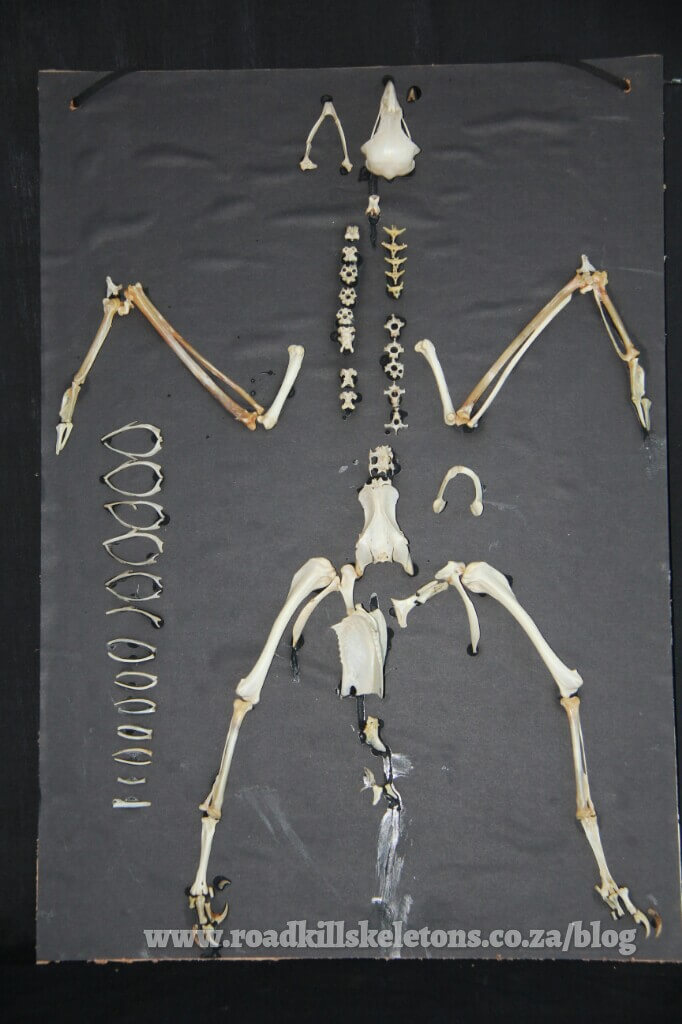

In the beginning all my skeletons were 2-dimensional glued on a flat piece of paper. Below is a skeleton of an Steppe Buzzard stuck on a paper. The skeleton is totally incorrectly put together, with the humerus in the place of the femur. I only realised the mistake many years later.

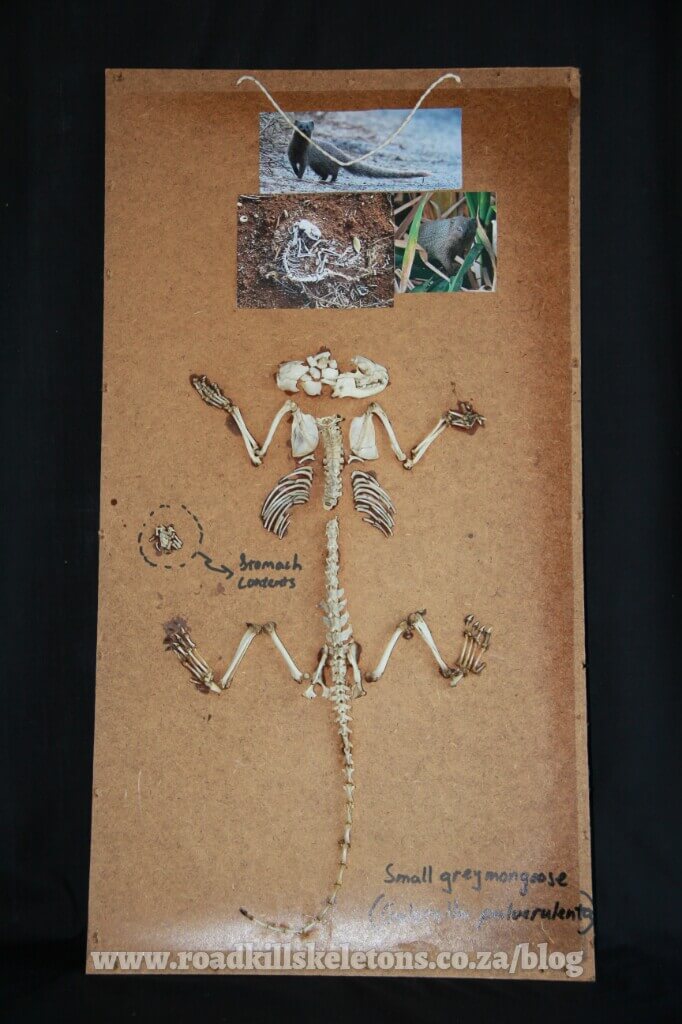

Below is another one of our first attempts. This one is a Small Grey Mongoose (Galerella pulverulenta) that we collected as a roadkill. My dad's rule was that we can pick it up and process it only if I learn everything there is to know about the animal. I also had to learn the scientific name. Something that I love doing is inspecting the stomach contents of the roadkills. In the picture below (on the left) is the skeleton matter of a rodent that this mongoose ate shortly before he was killed by a car.

Since building my first skeletons on a flat piece of cardboard, my hobby has progressed to the construction of 3-dimensional skeletons. However, finding a complete set of animal bones was not easy. Our first 3D skeleton was my pet rabbit that died of natural causes. At the time when we constructed the skeleton, my dad did not tell me that it was my pet that died 6 months before. He told me the truth much later and I was a bit angry but at the same time also glad that I had something to remind me of my rabbit. Below is a picture of my rabbit.

From the beginning our rule was that an animal will never be killed for its skeleton, so apart from the odd bird crashing into my bedroom window or a dead seagull on the beach, there were few new skeletons I could build. One day we were travelling to the West Coast, when I saw a dead animal lying at the side of the road. After begging my dad to stop, we noticed that it was a Cape fox. The fox was already decomposed and the flesh eaten by raptors or crows. The next step was to convince my mother to allow us to bag the stinking animal and take it back home. This was no mean feat, but my dad suggested we vote on the issue resulting my mom losing by 4 to 1. Below is a picture of our Cape fox. This is still one of my favourites!

While the road kills on the roads of the Western Cape did allow me to study the skeletons of various species, it is always with mixed emotions when I come across another dead animal killed by a vehicle. When retrieving the mangled body of a small spotted genet or a caracal, I feel sad that the animal had to die in such a degrading manner. However, this emotion serves as motivation to mend bones and reconstruct the skeleton, thereby restoring some beauty to the broken animal. Sometimes a zoo would donate an animal that died of natural causes and while this results in a perfect skeleton, the road kills provide a greater challenge.

Below, we are working on a caracal roadkill.

Today we have numerous skeletons and skulls of reptiles, mammals and birds. Most of these skeletons can be viewed at our RKS museum at Butterfly World, near Klapmuts in the Western Cape, South Africa.

In the beginning years of my hobby I probably didn’t realise it would become a big part of my life. I hope that I can one day be involved with animals or do something that relates to bones or animal anatomy. I am not sure what I want to become but I hope to one day make a difference in the world and educate people on the importance of wildlife conservation. For now, I am just enjoying the hobby and trying to learn as much as possible.

Barn owl catching the Cape golden mole.